As we near the end of the residency, I’ve mostly focused my efforts on writing documentation and policies for the State Library of Massachusetts. Prior to my project, there was limited or outdated documentation and no policies in place regarding the management of the library’s digital content. This is the position that many institutions are in when beginning to consider digital preservation; it takes a lot of effort and commitment just to begin, but it is important to do so. Writing both documentation and policies will hopefully go a long way in establishing a digital preservation program at the State Library.

Documentation

In addition to much of the documentation being outdated, there also seemed to be a disconnect between what the documentation said and what the library staff was doing in practice (a common issue!). The documentation needed to be updated to reflect current practices, to act as a record of the decisions we’ve made through this process, and to ensure transparency in the State Library’s activities.

Knowing that documentation was a key deliverable of the project, I tried my best to document my activities as I went. For example, after meetings with institutions such as the Massachusetts State Archives and MassIT (the Massachusetts State IT Department), I typed up and organized my notes, then made them accessible to staff members through our shared server. These conversations informed some of our practice and I wanted the State Library staff to be able to refer to these notes later if needed. I also documented the process of testing and selecting a tool for batch downloading PDFs. We ultimately decided to use DownThemAll, a Firefox add-on, but I researched a few other options first. I included my notes on these options in documentation as a record of the decision-making process. In the last month, I made sure to review these notes and update them, as well as create documentation for any missing pieces.

We now have documentation on processes such as web statistics, batch downloading, renaming files with the command line, using Archive-It, creating and disseminating a survey to state libraries and archives, and our outreach methods. I hope this will help staff members better understand the decisions we made, the approaches we took, and how they can build on the work we’ve done through NDSR.

Policy Creation

In addition to documentation, policies are an important facet of a digital preservation program. Among other things, policies explicitly state an organization’s commitment to a program or project and defines an organization’s role and operating principles.

I wrote policy statements for the State Library’s collection development activities and their digital preservation program. First and foremost, these policies are meant to be working documents that are continually reviewed and revised over time. These are starting points to build on as the organization changes over time.

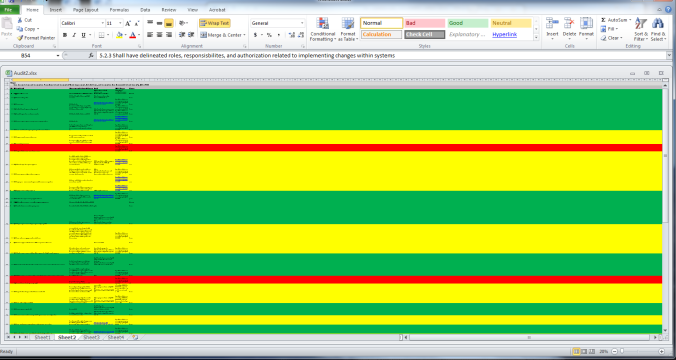

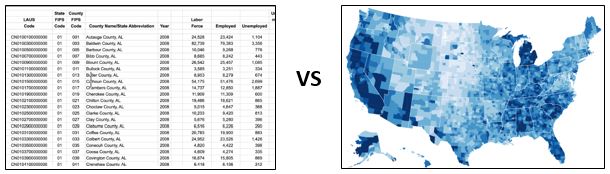

The collection policy statement is the culmination of what we learned through our analysis of the web statistics. After conducting the assessment, we had a list of the high and low priority documents we aim to collect and a description of the value-based judgments that led us to categorize documents this way. I feel that this adds a level of transparency not previously in place. This statement will be used as a guide when identifying and selecting valuable content moving forward.

The digital preservation policy statement describes the legal mandate that the State Library faces, the scope of the program, challenges faced, the roles and responsibilities of the State Library in tackling digital preservation, and more. Defining details such as the file formats we accept, our focus on collaboration, our intended audience, and our guiding principles allows the State Library to move forward in its efforts to preserve digital content with this as a reference guide.

Updating these policies or creating new policies as the State Library’s delves deeper into digital preservation is key.

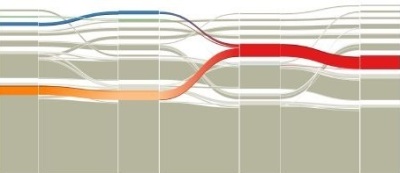

Early in the NDSR program, we, as a group, assessed our host institutions against a few benchmarks to get an understanding of where our organizations stood and to better understand the steps we should consider in moving them forward. Using the Five Organizational Stages of Digital Preservation benchmark, I concluded that the State Library was at Stage 2, meaning that they were advancing from understanding the need for digital preservation to taking on a digital preservation project (NDSR!). Though no formal policies were in place, the State Library understood they needed to better manage the digital content in their collections and demonstrated a commitment to doing so through participation in the NDSR program. My hope is that a successful NDSR project, an assessment of the scope of existing content, an increased knowledge of how similar institutions handle these tasks, and the development of documentation and policies will all assist the State Library advance towards Stage 3, in which they build a long-term digital preservation program.

My fellow residents and I will be presenting our project posters at Harvard on Monday, May 23 from 3-4:30. Check here for more information and hope to see you there!

Sources

Anne R. Kenney and Nancy Y. McGovern, “The Five Organizational Stages of Digital Preservation”, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=spobooks;idno=bbv9812.0001.001;rgn=div1;view=text;cc=spobooks;node=bbv9812.0001.001%3A11.